Before you ask, yes, there is an International Men’s Day. It’s November 19th. But today is the day we celebrate all things female. On a day such as this I could continue to plug my play about all-round Wonder Woman Eleanor Marx (that would be easy and fitting to do) or I could do something else. I have chosen to do something else. Something I never do. A thing that makes me a little nervous.

Below is a short story I wrote, set in Thatcher’s Britain of the 1980s, about a fifteen-year-old girl who has her first harsh brush with the reality of what it is to be a woman. I have many versions of this story — longer and shorter – the one I’ve posted here is a comfortably middle-sized version. (Apologies for lack of paragraph and dialogue indentations, they were there in the preview but gone when published).

THE WIG SHOW

By Lucy Kaufman

Whatever a Wig Show was, Penny thought, it certainly drew a crowd. She had never seen so many grey heads gathered in one room. Everybody else here, except for Jo, was old enough to be her grandmother. Penny re-clipped the pink rosebud in her hair twice and fluffed her corkscrew tresses around her shoulders. Then she smoothed her short denim skirt as far as it would go over the tops of her lightly tanned thighs, and crossed her knees. When her wriggling toes caught the overhead light she noticed the little semi-circular nails were the exact same pink as the butterflies on her shirt, and swirled pearlescent, like the undersides of shells.

Jo turned up the collar on her lemon shirt, Sloane Ranger style, flipped her shades down over her eyes and slouched into the hard pew, chewing on a Hubba Bubba. Jo may not have had the money or breeding of a Sloane Ranger, but in spite of her mere fifteen years she could turn her collar up and put on dark shades with the best of them.

‘Ladies, ladies, ladies!’

‘This’ll be interesting,’ Jo said.

All heads turned to see a woman enter clapping her hands with authority and striding down the aisle in her black pencil skirt and gold ankle-strap wedges, causing a Poison by Dior breeze and a flurry of chatter in the pews as she passed. Penny and Jo didn’t know she was called Marjorie then, but they soon gathered that was the case when her grey audience began clamouring her name, stretching out their hands to her, as if she had a part in Neighbours rather than being a presenter of a wig show.

Marjorie was as brown and wrinkled as a walnut, stick-thin and tottering close to six feet on those 4-inch wedges. Her hard, East-End face cracked stiff, burgundy Max Factor smiles at the end of every sentence that never came close to reaching her eyes.

‘Cleopatra’s seen better days,’ Jo said.

Penny sniggered into her fist.

It was impossible to miss the huge solitaire and cluster diamond rings from several marriages on Marjorie’s bony, saggy-skinned fingers or the oversized, brassy necklace with links like cobra-scales jangling from her leathery neck. But it was Marjorie’s hair that gave her the distinctive Cleopatra look. It was long and black, and dead straight, it’s full fringe finishing with level perfection at her kohl pencil eyebrows.

‘That’s a wig,’ Jo said.

‘Well, this is a wig show,’ Penny replied.

Jo leaned forward and peered through the gaps between the thinning salt ‘n’ pepper heads jostling above the pew in front.

‘Talk about a skeleton in shoulder-pads,’ Jo said.

Marjorie wasted no time in setting up her tables at the altar, arranging her array of flesh plastic heads with symmetrical precision before topping each with a wig from the vast collection lying dormant in her open suitcase: There were Farah Fawcett blondes with engineered flicks, long Karen Carpenter chestnut manes, Margaret Thatcher caramel bouffants and Mrs. Slocombe coiffured reds, and a million variant shade in-between. From whitest sand to darkest raven, from short elfin to down the back bum-skimming – they were all there. On a second table, Marjorie showcased wigs with levels of curliness from wavy through to curly through to downright bubble. She bristled with professionalism as she worked, bouncing greetings and snatches of conversation back and forth across the pews with the ease and skill of a table-tennis champion.

At last, Marjorie turned to her audience, clasped her hands together and twisted her long talon-tipped fingers into a complicated sailor’s knot.

‘Welcome to the Wig Show,’ she said. ‘What a pleasure it is to see so many familiar faces.’

It was a voice that could crack nuts.

Marjorie then proceeded to detail everything you could ever wish to know about the care and maintenance of her wigs. These were not any old wigs, she said, but wigs made from ‘real human hair.’

Jo’s jaws stopped chewing. She flicked up her shades and shifted upright.

‘Teen girls from Russia are queuing up to sell whole heads of it,’ Marjorie said, ‘the optimum age of these girls is thirteen. Once puberty has rampaged, well, you wouldn’t want to know…’

Someone in the front few pews mumbled something inaudible. Jo and Penny glanced fleetingly at each other.

‘Their loss is your gain, Margaret,’ Marjorie said, before launching in to the whys and wherefores of how to shampoo, brush and store your wig.

‘If you buy a longer wig it can be more versatile in the long-run.’ she croaked. ‘Should you get bored of it, simply pop along to your hairdresser and get them to style it for you. It can be cut and blown, or set in rollers, just as you would your own hair.’

She held up the Margaret Thatcher caramel number.

‘Never be afraid of your wig. You control it – don’t ever let it control you.’

Marjorie surveyed her room. Every single head was giving her their undivided attention. ‘Now, who’s for trying one?’

Marjorie was instantly descended upon by fifty doves-turned-vultures.

‘Calm down, calm down,’ she said. ‘There’s no hurry. I’m here till twelve.’

But she may as well have been holding back the queue outside the door of a jumble sale.

Jo sat gently blowing bubbles and Penny watched with cool fascination as Marjorie worked the crowd of women grabbing randomly at wigs and clinging onto them as if their lives depended on it.

Marjorie’s years of experience came to the fore.

‘You had that one last year, dear.’ ‘I know, sweetheart.’ ‘Perhaps this year you’d like to go a little more daring’, ‘Try this one. A tad bronzer’, ‘Towards the copper would look marvellous with your skin-tone. Bring out those gorgeous green eyes’, ‘Take your glasses off, sweetheart, let’s get the full effect.’

The women lapped it up, twirling their heads to their friends, receiving a shower of admiring compliments with every inch of a head-turn: ‘Gorgeous!’, ‘Beautiful!’ and from Marjorie, ‘Fabulous, sweetie. That IS you.’

‘Oh now, Maureen! Look, Bet, doesn’t she look adorable. That ash blonde suits her down to a tee. Doesn’t it just? To. A. Tee. Who knew you were a curly?’

The wigs were swapped around with gusto. One by one, the room of grey was transformed into a multitude of vibrant hues. And it wasn’t just the women’s hair that changed. Penny noticed the women’s faces began to alter, too. They began to have eye colours, of various depths and shades. Noses that had previously melded into the general gloom of their faces now stood out as hooked or button or pinched or Roman. Cheekbones appeared, eyebrows came into focus, face-shapes and distinct personalities emerged. Teeth became characterful, mouths animated and expressive.

It was as if Marjorie, with all her recycled hair, was giving them back their individual personalities and their characters. These women were becoming cheeky, mischievous, sprightly, sweet, their skin-tones now distinct from one another. This roomful of blondes, brunettes, red-heads. It was as if Marjorie had conjured them from somewhere invisible, and made them tangible again. And they were smiling, smiling, smiling.

‘You’re all beautiful,’ Marjorie said, clapping her hands together. ‘Beautiful!’

Cheques were written, wads of cash were handed over and immediately stashed in the elasticated pocket inside Marjorie’s suitcase. One, two, even three wigs at a time were paid for.

Penny’s eyes widened a little when she saw how much money these women were prepared to part with. Six hundred pounds a time! That was more money than Penny had seen in her whole life.

A man appeared in the doorway, looking a little ruffled. Penny and Jo turned to look.

‘I was told there was an emergency,’ the man said quietly, more than a bit relieved to see his wife alive and in one piece. He was soon informed the emergency in question was concerning a purchase she wanted him to make on her behalf, and further bemused by the cheers from the women that thronged around him and swept him into the room. They all but carried him above their heads.

The man, whose name was Don, was duly presented with the purchases his wife Joy wanted to make: a curly auburn wig and a Marilyn Monroe. They were laid out before him, like precious wares. The other women waited with expectant eyes and baited breath for him to give the nod. You could have heard a pin drop as he took on board what was being asked of him, and wrestled with his decision. Fortunately for Joy, Don was the Man from Del Monte.

‘Whatever makes her happy,’ he said, and reached in his blazer inside pocket for his cheque-book. There were whoops of endorsement all round. ‘Good old Don’, they said, ‘you can rely on Don’. Don wrote out a cheque for twelve hundred pounds, there and then. Before the ink had a chance to dry, the cheque was hastily passed, in relay, from woman to woman, to Marjorie on the other side of the room. Marjorie clasped the cheque to her bosom as if there had never been anyone so surprised by a person’s generosity, before squirrelling it away with the thirty or so other cheques, not to mention the piles of cash, in that bottomless suitcase.

Now it seemed everybody had made a purchase. All except Jo, Penny and one humdrum, gaunt woman they all called Daphne.

‘Poor Daphne hasn’t got anything yet,’ her friend, Sylvie said. ‘You must help poor Daphne out, Marjorie. Look at her, poor dear, she’s empty-handed.’ She then mouthed conspiratorially to Marjorie, ‘She’s a wig virgin.’

‘Oh, poor Daphne!’ Marjorie said, and she was not the only one.

Something of the Dunkirk spirit all at once rained down upon this wig show in Devon. Daphne, the only head over sixty that was still topped with its original grey, stood forlornly amongst the babble of her more glamorous counterparts, whilst everyone pulled together to ‘find her something.’

‘We’ll find you something, Daff,’ Sylvie said. ‘Don’t you worry. Look here, Daff, which one takes your fancy?’

There were still a few wigs left on the tables. The bolder colour choices, the longer, the curlier and straighter ones. Daphne looked at the leftovers on offer with the confidence of Bambi.

“I don’t know,’ Daphne said. ‘There are so many… which do you think?’

This was to nobody in particular, or perhaps more vaguely aimed at herself, but it was Marjorie who took it up as an invitation to start juggling wigs on top of Daphne’s head with the sleight of hand of Paul Daniels.

‘I don’t think dark,’ Marjorie said. ‘Or too light. Not with your hazel eyes. Are you a redhead?’

Marjorie scrutinised Daphne’s face as if the answer was printed there in a minute typeset, and settled on the caramel Margaret Thatcher wig.

‘Do you think so, Marjorie?’ Daphne said, screwing up her nose.

‘Absolutely. It says strong, it says classy, it says Daphne all over.’

‘Really? That’s me?’

‘The real Daphne.’

‘The real me?’

Daphne let out a nervous sound, somewhere between a giggle and a whimper.

‘Ted will love it.’ Sylvie said.

‘You think?’

‘I know it.’

‘Well he did once say I dress too dowdy.’

‘Exactly.’ Marjorie said, ‘Your husband sounds like a very sensible man. He knows a good thing when he sees it.’

‘He does…’ Daphne said, not even convincing herself.

‘He chose you, didn’t he?’ Marjorie said.

‘You’re right,’ Daphne said. ‘Ted will love it.’

And the perplexed look in her eye gave way to the beginnings of a sparkle.

‘Of course he will,’ Marjorie said. ‘What man doesn’t love his woman to get dolled up for him once in a while? It’s not all about putting the dinner on the table now, is it, ladies?’

She winked at Daphne.

‘Ted does like his dinner,’ Daphne said.

The women laughed.

Penny almost choked on her chewed-off fingernail.

‘Don’t take my word for it,’ Marjorie said. ‘Why don’t you ask Don? Don, dear, I am right aren’t I.’

All heads turned to face Don. Penny saw him physically squirm a little. The pressure of all those eyes made a bead of sweat break out on his liver-spotted forehead.

‘Absolutely. Joy still sets my heart aflutter. Even after nearly fifty years.’ He said it like a pro.

Everybody ‘awww’ed at that, before turning back to interrogate Daphne.

‘It’s not I don’t like the wig,’ Daphne said, ‘I think it’s lovely. It’s just…’

Sylvie filled in the blank for her. She said to Marjorie, through pursed lips, ‘It’s the money. Ted keeps a tight rein on the purse-strings.’

Daphne flashed a warning look at Sylvie. ‘Ted’s not made of money,’ she said. ‘That’s all. He’s sensible with it. Likes to spend it on only things we really need. Things like luxuries are…it’s six hundred pounds, Sylvie…’

Marjorie literally stepped in here, placing her body between Daphne and her friend.

‘Let me stop you right there, Daphne, my lovely.’ she said. ‘I understand. And it’s nothing to be ashamed of. You don’t have the bank-balance Sylvie has. Or Don. Everybody has their own personal sit-u-a-tion.’

‘They do.’ Daphne said, with some relief.

Marjorie took the Mrs. Thatcher wig from Daphne’s head. She was Daphne again. But the wig was not even back in the suitcase before Daphne piped up.

‘Well, we have a joint account, Ted and I …’

Marjorie stopped still. She stood combing her fingers through the wig like she was petting a favourite Shih Tzu.

‘I mean, I have a cheque book in my handbag.’ Daphne said.

Penny watched with her jaw suspended as Marjorie paused. She stopped fondling the wig and put up her fingers to pull the narrow bulb of her nose. Go on, Penny urged. Say it, then. Go on. Do it if you’re going to. But Marjorie didn’t bite. She just shook her head a little, very slowly, and cast her eyes down, smiling with the embarrassment someone would have if they were genuinely too altruistic to take money from a customer.

‘No, no, Daphne,’ she said, ‘These wigs are a huge investment. They are far more than a monetary, investment, true, but a monetary investment all the same. I appreciate that, despite the years of pleasure an item like this brings to a woman, it can also stir up emotions you would rather not have. I get that. It can be very scary to be this desirable, to exude this much power. It can be too overwhelming to go from the daily grind of housework to the full-on throttle of being the potent object of your husband’s desires. And not only your husband’s desires. Rekindling your youth is never for the faint-hearted. It is an investment a little too far for some people.’

God. she’s good, Penny thought. Even Penny hadn’t seen that one coming.

‘Oh, but not too far for me,’ Daphne said, right on cue. She snatched the wig from Marjorie and held it as if she feared it would spring to life and tell her she was not one of those people. ‘I really do want this wig, Marjorie.’

Sylvie clapped her hands, in quick short bursts like an excited girl guide. Marjorie cocked her hand in the air and shrugged with the audacity of someone who had been defeated. Daphne flapped open her faux leather handbag and whipped out the cheque book to her joint account, and Marjorie silently placed a silver biro in her hand.

‘You won’t regret it, Daff, love.’ Sylvie said, ‘Ted will be chuffed.’

Marjorie slung the remaining wigs into the suitcase, slipped the cheque from Daphne’s trembling fingers and snapped shut the suitcase lid over it. She turned to her ecstatic audience one final time and waved the women to a resounding silence.

‘Thank you for coming, ladies,’ she said, ‘and remember: wear your wigs with pride.’

‘Let’s play Spot the Wig,’ Jo’s father said.

‘I beg your pardon?’ His wife said. ‘Spot the what?’

‘Spot the Wig.’ He said again, chuckling this time, his knife poised in the air, ready to saw his steak. ‘Well every single female in here’s bought a wig today, haven’t they? That’s what the girls said.’

‘Every female except us,’ Jo reminded him. ‘Where did the ketchup go?’

‘I think Terry whipped it for another table, Joanna.’ her dad said, eying Jo as he said so.

Penny was sure he had just about resisted saying ‘your Terry’ but the sparkle in his eye as good as said it.

Jo’s cheeks deepened into one of her infamous blushes.

‘Let’s play then,’ Jo said.

Penny and Jo’s eyes darted about the ballroom. The polished dance-floor was clear but on the raised, stepped platform around it, a few families on tables for four and six spoke and ate steadily, swapping stories from their day. Black-tie waiters, stiffly upright in their sharply pressed trousers, circled fluidly around the ballroom from table to table, each in their own private Viennese Waltz as they stacked plates, fetched jugs of water and located spare cutlery. Penny could see Terry hovering by a far-off table, laughing punctually at the tired punchline of a middle-aged father. From this far across the room, with his trim dark hair, white shirt and black bowtie, Penny thought Terry could almost be handsome. She didn’t need to look at Jo to know she would be following him around the room instinctively. She could see it in Jo’s little self-conscious fumbling with the pepper-pot and the clipped, shrill way she was speaking to her father.

‘There’s one,’ Jo said, jutting her head towards one of the tables for two.

They all looked to see a couple at a table, either side of a single rose in a vase, staring down at their plates and clinking their knives and forks without speaking. The man, in his late sixties, was dressed in battleship trousers, a v-neck tank top and a tie. His thinning grey hair was slicked back with something that greased it to a glaze over a bald patch. Penny recognised his wife from the Heraldry room, more by the wig than anything about her. She was wearing one of the sleek bobs, in a honey colour.

‘So there she is, our first spot.’ Jo’s father said, to which his wife gave a small tut, so small you might have missed it, if it hadn’t been accompanied by a half-turn of her head in the direction of the woman in the sleek bob.

‘So she really is wearing it!’ Penny said, the words gushing out with more surprise than she expected.

She sluiced the ice in her coca-cola, wondering what the hell she had thought the women were going to do with them. Hang the wigs in the wardrobe and open the door to just look at them now and then? She sipped from her glass as if to shut herself up.

‘That’s got to be a wig!’ Jo’s dad said, looking into a far corner.

‘Yep.’ Jo said.

Penny nodded.

It was the red bouffant Mrs. Slocombe.

‘A bold choice,’ Jo’s dad said, his bottom lip over his top in serious contemplation.

‘Who are you now?’ Jo said to him, ‘The wig judge all of a sudden?’

Jo’s mother laughed. It marked her entrance into the game. Now she too began looking from table to table, scrutinising the hair of the female diners.

‘Now that is definitely one,’ Penny said, looking over at a table on the far side of the ballroom.

Again, she recognised the wig before saw the face of its wearer. Unaware they were all turned towards them, watching them eat, the woman and her husband exchanged inaudible, formal pleasantries as they picked up and set down their wine and beer glass and piled restrained amounts of food onto forks and discreetly popped them into their mouths. The woman gave off an air of a knowing pride in herself as she ate, in her flouncy, nautical blouse, with her gold bangles falling up and down her lean, crinkly arm, and in her wig of course.

‘Has he even noticed that she’s got a dead poodle on her head?’ Jo’s father, said.

‘Shh, Tony. Keep your voice down, they’ll hear you.’ Jo’s mum said, and she was back to – pretending, Penny thought – not being part of the game.

‘But it’s so obvious,’ he carried on, studying the poodle-headed woman for longer than was polite before narrowing his eyes at his daughter. ‘Are you sure they’re real hair?’

‘From Russian children,’ Penny said.

‘That’s Gorbachev for you,’ Jo’s father said.

At every table for two, it seemed, there was a diner concealing her real hair.

Penny looked hopefully around the ballroom for Joy and Don. But of all the couples at all the tables for two, symmetrically seated on either side of an identical rose, Joy and Don were not among them.

‘Perhaps Don’s got lucky,’ Jo’s dad said, flapping his elbow in a nudge-nudge-wink-wink when Penny mentioned it to Jo.

Jo pulled a face and said, ‘Please’.

Her disgust turned to horror when she saw Terry marching towards their table, a white linen cloth folded over his arm, quite formally, his bowtie a little skew-whiff.

For once Jo managed to hold it together, blush-wise, as Terry scraped their mains from each of their plates onto a tea-plate. Penny had never known the transfer of a few peas could be so excruciating. Jo’s head was bent, twitching every now and then but able to flick her eyes up with the appropriate amount of politeness as she said, ‘thank you,’ when her plate was taken.

Penny watched Jo’s father as if she was expecting something to happen. Thinking he would say something. What exactly? She didn’t know. But she was sure there was some line ready at his lips that he was about to throw at Terry that would trip him up and send him sprawling. And then Jo would have to jump in to save him and then it would all come out, unravelling in one horrible ball of filthy string that was the Victorian kitchen garden.

But if Jo’s dad was planning on saying something, whatever it was never passed his lips. It didn’t need to. It was hanging in the air as thick as the soup Terry had served at their first lunch of the week. The tomato soup when Terry hadn’t known what a crouton was and had been wounded by the sharp edge of Jo’s dad’s tongue.

Luckily for Terry, and Jo, her father’s attention was diverted by a small commotion caused by an elderly couple entering the double doors of the dining room and having difficulty securing a table. As Jo’s family turned to see what all the fuss was about, Terry took his chance to dash to the kitchen.

‘I have never known anything like it in my life,’ the man was saying, when he and his subdued-looking wife were eventually seated three tables away from Jo’s family.

‘It’s Daphne,’ Jo whispered.

Penny nodded. She had clocked that too, the unmistakeable Margaret Thatcher wig giving her away without the shadow of a doubt.

Daphne was dressed in a fawn shin-length cotton dress and white roman sandals and was more heavily made up than she had been at the Wig Show but she still wore the same apologetic expression, and of course, the wig, perched on top of her head like a birds nest. Across the table from Daphne, her husband continued to puff about the maitre d’ as he plonked the vase with the rose to one side and swept the table-cloth with the flat of his hand as if it was personally responsible. He then sat with his body half a turn away from Daphne, one grey trouser leg folded over the other, his loose foot jangling in its polished shoe against the table-leg.

‘That must be Ted,’ Jo said. ‘Her husband.’

‘Good to see that school’s paying off, Christine.’ Jo’s dad said to his wife.

Ted was a small, slight figure in a pastel golfing jumper, who had quite a brush of white hair and a white toothbrush moustache that bristled as he spoke.

‘How could you be such a silly fool, Daphne?’ he said.

Penny was pretty sure everyone on the nearest tables heard it. Daphne must have heard it too, Penny thought, although she sat with her head bent over her menu, glasses on the end of her nose, her finger running over the print as if reading it in Braille.

‘Of all the daft…ridiculous…things. What the hell were you thinking of?’

Daphne twitched her nose, rubbed it on her knuckle and then clasped her hands together in her lap.

‘I’m sorry, Ted. I’ve said I’m sorry, but it’s too late to get a refund now, I’ve taken the label off, I’ve worn it. It’s used goods.’

‘Well you can get the thing off your bloody head for a start. I never want to see it again, unless it’s going down the road in a bloody dustcart.’

Penny saw a family on a neighbouring table set down their cutlery and chew in slow-motion, totally unaware of themselves or their open mouths, their eyes on Daphne and Ted as if they were at home with their plates on their laps, watching the telly.

Ted slid his menu aside and folded his arms, tight and high on his chest and shrank back in his seat. Daphne’s hand began scratching the tablecloth, as if scraping off something that was stuck there. Penny thought she saw her gulp.

‘Can’t I just wear it, tonight, Ted?’ Daphne said. ‘It’s our last night.’ Daphne’s voice was a very tentative voice, the voice of someone who was used to being defeated. ‘I may as well get my money’s worth.’

‘My money’s worth.’ Ted said, beating his chest with his pointing finger. ‘When you’ve earned it, Daphne, you can spend it.’

‘Stop it.’ Daphne said, ‘Everybody is looking at us.’

The whole restaurant was.

‘Let them look,’ Ted said, ‘You know what they’re looking at? They’re looking at you, you fool. They’re looking at that silly thing on your head. They’re thinking what I am. That it looks bloody ridiculous.’

‘I did it for you.’ Daphne said. ‘I thought you’d like it.’

She sat fingering the stem of the rose in the vase, all the time looking crushed by the weight of her mistake.

‘For me?’ Ted burst, ‘How the bloody hell is this for me, you silly moo? You’re not twenty anymore. You’re nearly seventy, for god’s sake. Don’t you know? Can’t you see it? Everybody is looking at you and they’re laughing. They are thinking exactly what I am thinking, that you’re an old woman. A wrinkly old woman in a stupid wig. That’s what you are. An old woman, Daphne. In a wig!’

Penny all but gasped. Jo’s mother picked up the dessert menu. Jo’s dad turned from table-watching to his family with his eyebrows arched high on his forehead. Jo fiddled with her bracelet.

Daphne let go of the rose stem as if its thorns had just pricked her. Ted leaned forward, a slow sneer spreading across his face.

‘You’re mutton dressed as lamb, woman.’ he said, in a low voice, although everybody in the room seemed to catch it. And then, as if to underline it, he cried out, shaking with rage, ‘MUTTON DRESSED AS LAMB!’

Daphne slid her chair back with a resounding scrape, tears springing to her eyes, and wrenched the wig from her head. It peeled away from her, painfully slow, grips and all, and she slung it down on the table. And then she fled, naked and grey in her own hair, her roman sandals scurrying across the ballroom floor. Ted shifted in his seat a little, sniffing periodically and staring ahead at the gaping void, quite alone at his table-for-two. Penny thought the rose in the vase seemed somehow redundant, and the caramel wig lying prostate on the table-cloth, as inanimate as roadkill, was worth less than the day it had been clipped from the head of the girl it had come from.

The bang of the double-doors as Daphne left seemed to be the cue for the whole restaurant to resume their conversations, along with their meals. At once a hum of chit-chat rose above the clatter of cutlery on china.

Penny looked at Ted, then from table-to-table, diner-to-diner, at wives still sitting in their wigs with husbands still seeming to ignore them. Daphne and Ted were forgotten, and the diners carried on the intricate minutiae of their lives.

All but Penny.

Penny sat very quiet for a moment, her fingers pressed to her temples. She could not clear the fuzziness in her head to think straight, let alone speak. And now she felt a swathe of sickness flood through her. A huge chasm had opened up between Ted and Daphne right in front of Penny’s eyes. And Penny had not only fallen in but was drowning there.

Penny looked from Jo, her golden head bent over her menu, to Jo’s mother calmly reading out the desserts in a steady tone, and Jo’s father, deliberating between a lemon meringue pie or cheese and biscuits. How could they do that? Just go back to their meal without a thought, without as much as a word, as much as a comment.

Of course, Penny thought, with a jolt. It was obvious. She watched Jo’s mother pour herself another wine. She knows. And Jo’s father – he’s a man. Of course, he knows. Probably Jo knows too. Penny stared hard at her friend. Yes, even Jo. They all know.

Penny found her feet and said in a voice barely above a whisper, ‘Do you mind…if I get some air.’

‘No, no, of course not,’ Jo’s mum said. ‘What’s the matter, love, aren’t you well?’

But Penny couldn’t answer. She didn’t have the words. There were no words. Not words that anyone would make head or tail of. She could only shake her head. She could only get out of there.

Penny crossed the ballroom floor with her arms outstretched, as if feeling her way through a fog. As she meandered through the entrance hall and vaguely headed for the exit, a couple were struggling with the weight of the French doors.

It was Don and Joy, dressed for dinner. So there they were, Don in a suit and Joy in a silk neck scarf and flashy jewellery. And they were together. Penny looked up at them as she held the heavy door for them, and smiled a broad, relieved smile. Joy barely noticed her as they breezed through in single file. But Penny noticed Joy well enough. Joy’s eyes were dead. Don’s eyes were deader still. And Joy was wearing neither of her wigs.

‘Well we could have, couldn’t we?’ Don was saying, as they walked away from Penny towards the double doors of the restaurant. ‘If I hadn’t had my arm twisted I’d still be twelve hundred pounds richer.’

Penny dashed through the French doors and out, out onto the terrace, the humid night air engulfing her lungs.

So now she saw it as it really was, she thought, as everybody else had already seen it. The truth. The stifling air constricted in her throat. She tried to gulp down breaths but the night air was too still and too close to give relief. This was marriage. This was love. This was it and it was as ugly as decaying flesh. And she, Penny, was the very last person in the entire world to know.

She looked behind her, to the paved terrace outside the restaurant, bounded by its high strings of fairy lights. The terrace, like a fairground, was sad and abandoned in the daylight, but at night, at night when the lights were flicked on and the string quartet took up their bows, it was beautiful. Perhaps she expected to see Jo and her mum and dad come rushing out of the French doors and down the steps towards her, full of anecdotes, and gossip, but they didn’t.

There were no families at all on the terrace, only couples, in their twenties and thirties – men in summer suits, with wide smiles and women in fitted, satin, dresses with tinkering laughs, dotted along the open-air bar, on stools, or standing, sharing private jokes, and fleeting looks, over glasses topped with umbrellas and cherries on sticks. Tuxedoed waiters skirted around the couples, like penguins on ice, offering little somethings on balanced trays that Penny would later learn were canapés, but she didn’t know that then.

How could she?

How could she?

Watching the couples, far off, in their fairy light world it all slipped away from her as if it never existed. As did Ted, as did poor Daphne. Poor Daphne. They all faded from her view.

Gone.

Penny turned to the black lake and looked out to where it joined the black sky. The sky and the lake fused together in a seamless whole, a single black velvet cloak, the stars winking down at her like the diamond shards of brooches pinned there. And then she felt it, a rush, starting at the base of her stomach, creeping up and taking hold in her chest and bursting there. Bursting exactly as if she was enveloped in that cloak and lifted high into the black, to converse with those stars.

All this was to come, she thought. All this: still to come.

She pictured herself, on a pine-fringed coast, standing as she is now only taller, in a red satin gown, looking out over the waves of the Mediterranean perhaps, or the Aegean, and tasting the salt in the breeze in her hair. She is sipping something intoxicating from a pretty-shaped glass, the dizzying warmth of fingertips on the small of her back. She sees him turning her face to his. A face yet unknown. She is smiling, laughing. She knows. She is certain. He is out there somewhere, beneath identical stars.

And all this. It is waiting for her. The wheels are already set in motion, and not a soul alive can stop them.

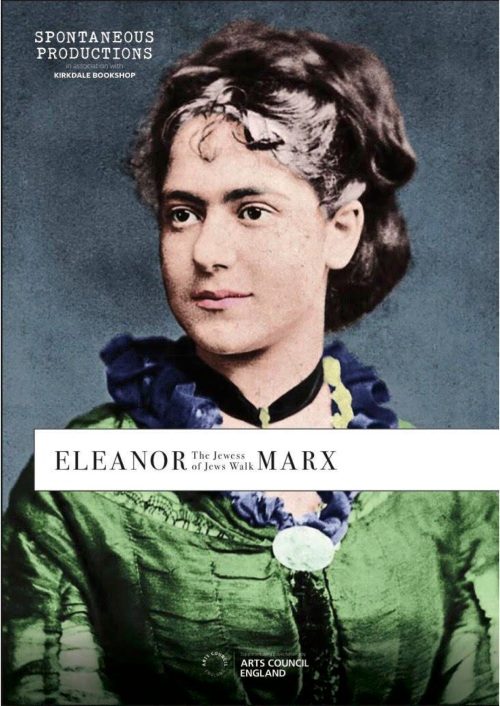

We are now halfway through the run of the world premiere of my play Eleanor Marx: The Jewess of Jews Walk. So far we’ve had fabulous audiences, wonderful feedback and some amazing reviews (Spoiler alert!):

We are now halfway through the run of the world premiere of my play Eleanor Marx: The Jewess of Jews Walk. So far we’ve had fabulous audiences, wonderful feedback and some amazing reviews (Spoiler alert!):